It is so very easy to be critical of the commodification of sports: the amount of money in boxing that has reduced it to prize fighting, the glitz and distractions of the IPL, the ugly circus of football clubs being bought by billionaires and treated as trophies. All of that is true. Capitalism corrupts everything. The amateur player feels the pressure to go professional because that is where the money can be made. Working-class youth pushed into sport as the upward ladder for mobility. Money flowing from corporations so that their logos can festoon the Formula-1 cars and the buntings on the side of the hockey field. Money dowsing players who walk onto cricket fields to the throbbing sound of an Ibiza disc jockey. But this corruption of money is not isolated to sports but is general in a capitalist society. It is merely that one is most disgusted with the level of money in sports because of an ancient purity that is accorded to the athlete, a pure figure of human ability who can do things that cannot be done by other mortals.

Underneath the corruption of money remains something quite genuine: the human attributes that makes games a great diversion if one is on the field or if one is in the stands. A ball that deceptively swings in the air and forces a batter to play at it and send it scuttling into the hands of a quick witted first slip fielder; a kick that sends the ball hurtling toward the far goal post but is intercepted by a lunging goalie. There is poetry in such athleticism, the crowd on their feet to cheer on the players even if it means the defeat of one’s own team.

Revolutionary Jab

For many years now, I have been working intermittently on an essay-length book on the Cuban boxer Teófilo Stevenson (1952-2012). Stevenson won the Olympic Gold Medal in the heavyweight category at Munich (1972), Montreal (1976), and Moscow (1980), and – without question – would have won the medal at Los Angeles (1984) had Cuba not boycotted those games. Stevenson came to boxing like many young men around the world, to get out of poverty. In the years before the Cuban Revolution of 1959, Stevenson followed his father into building up the skills of prize fighting, but then after the Revolution changed its theory of sport, he went to train at the Escuela de Boxeo in Havana under the watchful eye of the Soviet boxer Andrei Chervonenko after May 1969. Years later, Chernvonenko recalled his first encounter with Stevenson:

===

I saw Stevenson by chance during a trip around the country. I remember being astounded by his physical condition, his cautious way of fighting, and his terrible technique. I immediately proposed including him in the national team. There was some opposition. They saw him as still too raw. They suggested he lacked toughness and aggressiveness. I had to explain to them that caution has nothing to do with cowardice. Stevenson trained with great zeal. We emphasised giving him a good punch with a direct left and a direct right hit. We improved his defence. He advanced.

In 1962, Cuba banned professional sports and championed sports as a part of public health. A few years ago, in the national office of the Institute of Physical Education and Recreation (INDER), its vice president Raúl Fornés Valenciano told me that because Cuba decided to invest in sports, it has less health problems. Across the country, INDER focused on getting the entire population active with a variety of sports and physical exercises. Today, over 70,000 sports health workers collaborate with the schools and the centres for the elderly to provide opportunities for leisure time to be spend in physical activity to prevent chronic diseases from harming the population. This has been the character of Cuban sports – geared toward health more than toward the corruption of money.

Stevenson is an icon of this form of sports culture. He was a remarkable boxer, cautious – as Chernvonenko put it – but not a coward. The best boxing, which is often on display in lower weight categories, is not about violence, but about timing and stamina, the skill to be watchful and to hit when there is an opening and to defend at all times. Brashness is the culture, so that the boasts and dancing of Muhammed Ali (1941-2016) was celebrated, but this brashness should not be mistaken for recklessness. The skill of the boxer comes with patience. In his epic essay on Archie Moore (1913-1998), A. J. Liebling writes that Moore was ‘the most premediated and best-synchronised swayer in his profession’. In other words, during his fights, this light-heavyweight champion would allow his opponent to try and hit him with all energy, and he would merely sway out of the way of the punches; it is less tiring to sway than to punch, which would eventually exhaust Moore’s opponent and open him up to Moore’s quick jabs. The swaying was the strategy, Moore’s stamina more closely harnessed than that of the reckless fighters he faced. Ali was the same. Bouncing around, dancing in the ring, flying like a butterfly, and then when it came time, stinging like a bee. Stevenson knew when to marshal his strength and when to use it. Those who claim that boxing is just brutal have never seen a boxer like Stevenson dance in the ring, his size diminished by his grace.

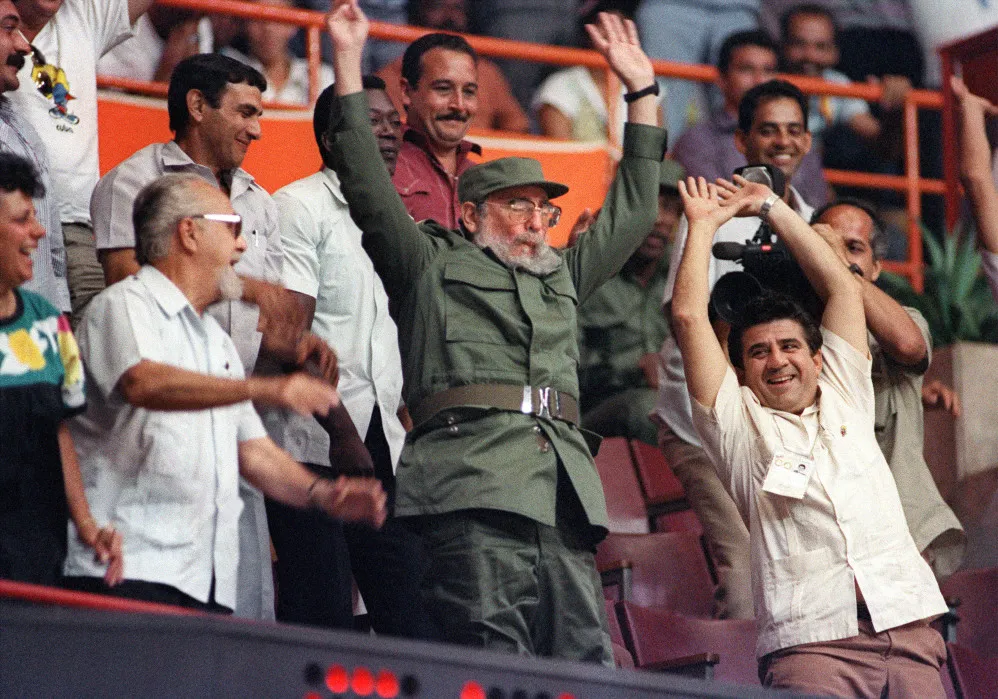

Ali desperately wanted to fight Stevenson. He said that he would do anything to be in the ring with the Cuban. Money was put on the table. A lot of it. But Stevenson refused to break out of the Cuban amateur culture. ‘What is one million dollars compared to the love of eight million Cubans’, he said. When asked what he thought about sports in the West, Stevenson said that ‘sportsmen in the West under capitalist are a commodity’. He was a man, a Cuban man, and not a commodity. That is the essence of the class struggle in sports: the player who wants to play, and who wants to be a human being and not a commodity.

To play. At the Cuban boxing school outside Havana, I walk through the training ring and feel the energy of generation after generation of great fighters. Walking alongside me is the tremendous Julio César La Cruz, who won the gold medal at the 2016 (Rio) and 2020 (Tokyo) Olympic Games. Cruz, known as La Sombra (The Shade), is a big man with a large smile that flashes his gold teeth. But like a man of his size and strength, he is gentle. He took me back to see his room in the school, and gave me his gown from the Tokyo Olympics. On his bed, he had festooned an army of stuffed toys, with Sponge Bob on the front. He was proud of his room, his gentleness characteristic of so many boxers. There is nothing violent in his body, and indeed in his technique. He carries the name La Sombra because in the ring he is hard to see, elusive, quick, darting out of the way, tiring his opponent with his shadow presenting itself before his body. At the Tokyo Olympics, Cruz defeated the Cuban born Spanish boxer Emmanuel Reyes in the quarterfinal. Reyes said after the fight, patria y vida, a slogan attributed to the anti-Cuban Revolution ranks. Cruz was quick to set that aside and said, Patria o Muerte, Venceremos, the slogan of the Cuban Revolution. There was no necessary animosity in this exchange. It was simply a difference of opinion about their birth island. Reyes had left for the money, but claimed that the money was life (vida), but Cruz stayed for the fight until death (Muerte) if necessary. Like Stevenson, Cruz is not interested in being a commodity. He wants to be a man.

‘I ain’t never liked violence’, said Sugar Ray Robinson (1921-1989), one of the greatest boxers of all time. Robinson fought 201 times, winning 174 of them. But of the wins, he won by knockout 109 times (many of them in the first round), a remarkable bunch of numbers that had been sustained by Robinson’s legendary left hook. But this man – who took time off from his boxing career to become a professional dancer – did not like violence. Watching a fight produces a strange reaction: there is the constant fear of a lethal punch hitting the face of a careless fighter, but at the same time there is the anticipation of the left hook coming in fast and the fighter ducking it and moving forward to jab into the stomach. There is no wonder that at the fight, the audience cannot sit back but leans forward, watching every motion, every muscle move. This is not a gladiator’s contest; this is a dance.

La Sombra is walking with me across the tree-lined road in the boxing school. He takes my hand in his and squeezes it. I can feel his strength but also his kindness. I realise that this is the hand that became a fist and – as he backed away with that characteristic dance style of Cuban boxing – pummelled Russia’s Muslim Gadzhimagomedov in the face in the final of the Tokyo Olympics. I squeezed his hand back. He smiled gently at me and told me a little about his childhood and his dreams. It was not money that he coveted but, like Stevenson, the love of his people. What is $20 million compared to the love of eleven million Cubans? Cruz has already won that with his humility and his skill, the essence of boxing and sport.

Vijay Prashad is a Historian and the Executive director of Tricontinental Institute for Social Research.